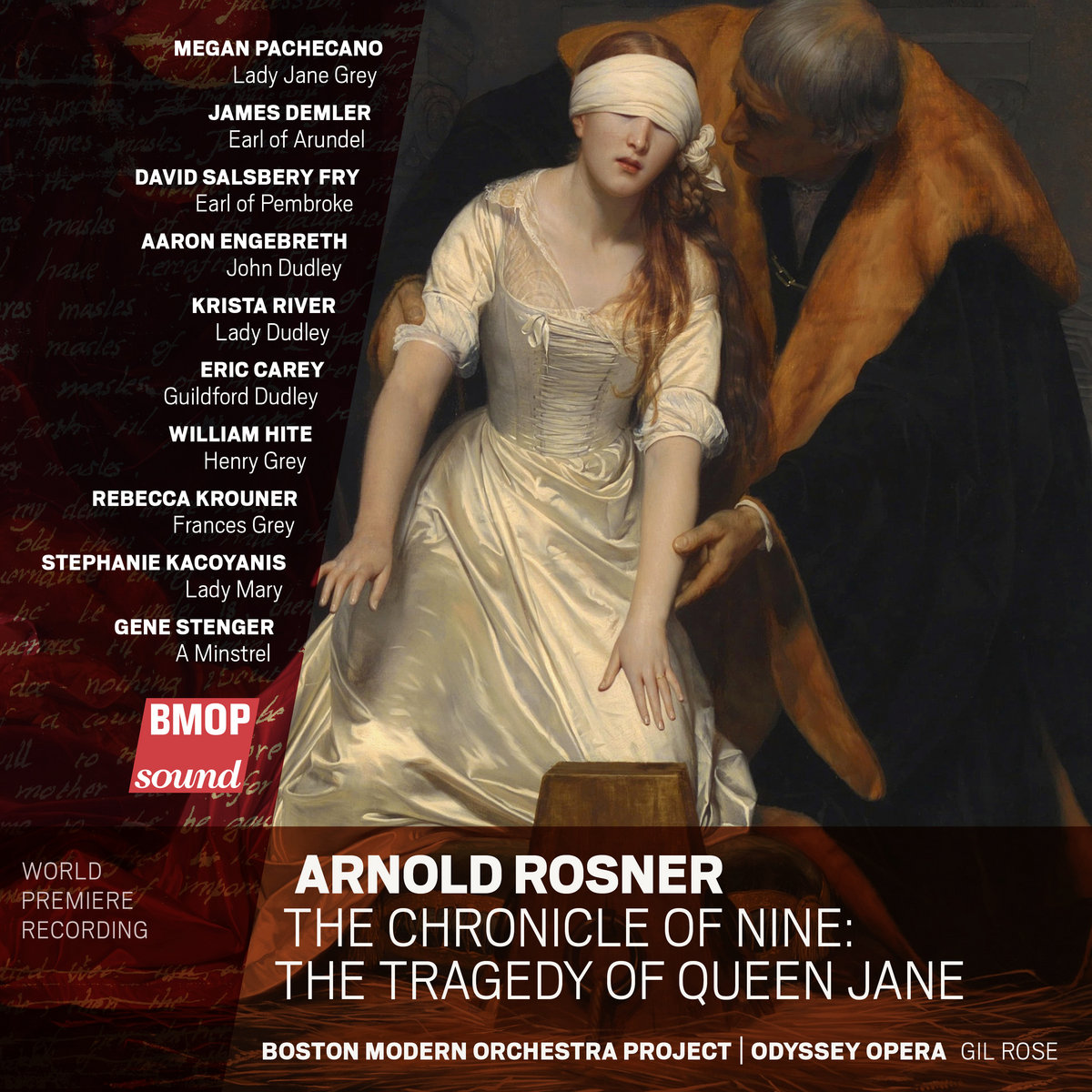

ROSNER: The Chronicle of Nine -- The Tragedy of Queen Jane (1984).

Megan Pachecano (soprano, Lady Jane Grey); James Demler (baritone, Earl

of Arundel); David Salbery Fry (bass, Earl of Pembroke); Aaron Engelbreth

(baritone, John Dudley); Krista River (mezzo, Lady Dudley); Eric Carey

(tenor, Guildford Dudley); William Hite (tenor, Henry Grey); Rebecca

Krouner (contralto, Frances Grey); Stephanie Kacoyanis (contralto, Lady

Mary); Gene Stenger (tenor, Minstrel); Odyssey Opera; Boston Modern Orchestra

Project/Gil Rose.

BMOP/sound 1081 (2 disks) TT: 81:36 + 49:42.

BUY FROM BMOP

Monumental, unfortunately. American composer Arnold Rosner's career suffered

from mainly two things. First, his idiom was out of joint with the prevailing

post-Webernian serialism and avant-gardism of the time. Second (and related

to the first), he had few connections to those musical circles that would

have led

to big commissions and performances. Against this, however, he also had a burning

conviction -- largely clear-eyed -- that he was a great composer. I agree with

him. At his considerable best, which was often, he turned out masterpieces

-- chamber, orchestral, choral, vocal -- and the best thing about them

is that,

despite their considerable compositional complexity, they speak directly to

listeners. I often wonder what the premiere audience at Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra

felt. That score became an instant classic. Those feelings stirred in me when

I heard the majority of Rosner's recorded output for the first time. He has almost

everything I want. The music takes big, epic strides. The ideas and their development

speak directly. The "narrative" proceeds clearly. The idiom, though

eclectic, in toto belongs to Rosner alone, as Mahler assimilated Wagner, Bruckner,

Brahms, the German Lied tradition, and folk song to forge something instantly

recognizable and unique. Rosner takes big aesthetic risks.

At the same time, I recognize Rosner's limitations. He gravitated toward the

grand, even the grandiose. One meets with few "light" pieces, although

they sparkle with wit and good humor. He could write them, but his artistic

sensibility resonated more with rarified emotional heights. He began an opera

on Bergman's

The Seventh Seal, writing a good deal of music before Bergman denied him permission

to use the script.

In the wake of Bergman's shutdown, Rosner cast about for another subject, suitable

for the grand opera he wanted to write. He found one in a modern verse drama

by Florence Stevenson on the nine-day reign of Lady Jane Grey, which (with

Stevenson's permission) Rosner adapted to a libretto. The story concerns the

bloody Tudor

politics following the death of the boy-king Edward VI, Henry VIII's heir.

Jane Grey, a teen herself, is pressured into a marriage with the powerful Dudley

family.

That faction proclaims her Edward's lawful successor. Unfortunately, they have

little popular support and Jane is deposed in favor of Mary Tudor (known as "Bloody

Mary" for her persecution of Protestants; she was, of course, Catholic).

It wasn't a matter of religion for most of the English, but the fact that they

regarded Mary as next in the rightful line of succession. Mary imprisoned Jane

and her husband and executed them both, along with the other major players

of the Dudley faction. It took Rosner four years to finish this, his longest

score.

Most composers fall into either the lyric or the dramatic category. The

lyric composer directly expresses emotions. The dramatic composer creates

characters

and emotions rise from conflicting points of view. It is the difference between

a Keats sonnet and a Chekhov play. Mozart could do both. The Symphony No. 40,

while turbulent, is lyrical. The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni -- although

both contain beautiful arias -- not only depict character but provide a variety

of pace that moves the action along. Rosner, despite the "drama" in

his instrumental music, remains a lyric composer, not a dramatic one. His musical

methods don't really suit the theater.

Nor does Lady Jane make a strong heroine. Historically and dramatically,

she has little agency, essentially a cat's-paw for the bigger players.

That's not

necessarily a bad thing, if you can breath life into the intrigue. This Rosner

fails to do. Each scene moves at roughly the same slow, steady pace. The musical

variety comes from instrumental interludes and preludes. Furthermore, each

character sounds like every other. Dramatically, the opera fizzles out. This

doesn't mean

it lacks effective moments, like Jane's prayer (Act I, scene ii), the love

duet in the Tower between Jane and her husband (Act III, scene ii), the powerful

final

scene of Jane's execution, or any of the instrumental pieces, but these again

are essentially lyric, not dramatic. It's a bit like watching a pageant, rather

than a play.

I should add that Rosner succeeded in his short opera, Bontsche Schweig

(based on a short story by I. L. Peretz, never commercially recorded),

mainly because

it's brief and because the nature of the original story is more ritual than

drama. Rosner never heard this score as a fully staged production. He did extract

bits as suite and reworked much of the music into his Seventh Symphony, and

both appeared

on CD. Kudos to the Boston Modern Orchestra Project and Odyssey Opera under

the direction of Gil Rose for championing a score which, even now, has very

little

chance of a path in the "normal" opera world. The notes, by Walter

Simmons and Carlton Cooman, and the sonics are first-rate. Although I think

it a weak opera, it still contains marvelous music. Rosner can still get to

you.

S.G.S. (April 2022)